The Making of a Winning Term Sheet: Understanding What Founders Want

Part I. The Special Founder Liquidation Preference

By: Jonathan D. GworekJune 07, 2007

Introduction

Know your target market. It is one of the most fundamental principles of any successful marketing strategy. Investors who understand what the founders of a startup really care about will stand a better chance of winning the competitive deal.

Currently when competitive situations arise, most venture deals are won and lost on the basis of pre-money valuation and the perceived reputation and fit of the competing venture firms. Winning deals on the basis of aggressive pre-money valuations is a one dimensional strategy that relies on speculative information about competing offers and can drastically impact return on investment. Younger, smaller venture firms that are still establishing their place in the market are often not able to compete on reputation. In an investment environment in which too much money is chasing too few deals, venture firms may be well served to think creatively and act proactively in crafting term sheets that are attractive to founders. Several deal terms can be modified with this objective in mind without significantly affecting an investor’s return on investment. In the end, giving up marginal deal protections will prove a shrewd strategy if the result is a stronger portfolio of companies.

A number of creative approaches to standard terms and conditions will capture the attention of founders. This is the first of a series of articles that will describe a few approaches that venture investors might consider using to enhance the chances of winning a competitive deal.

Special Common Liquidation Preference

The Overhang Issue. One common concern that founders express when considering whether to take venture money is the impact that the venture investor’s “liquidation preference” will have on the founders’ ability to realize a return on their common stock. The typical venture deal provides that upon the sale of the company the preferred stockholders will receive their money back first, plus often a dividend return, before any proceeds are allocated to the common stockholders. The result is that in certain scenarios the holders of common stock, including the founders, will not receive any of the sales proceeds. As rounds of funding stack on top of one another — Series A, B, C, etc… — this liquidation preference “overhang” can become quite stifling to the holders of common stock leaving little hope of any meaningful return for founders other than in the most optimistic of exit scenarios.1 Sophisticated or well advised founders are very sensitive to this overhang and it is one reason that some founders resist venture money altogether. The overhang can also create a misalignment of interests between the venture investors and the founding stockholders because acquisition scenarios can occur in which the common stockholders will not receive any proceeds for their stock, but in which the investors get a substantial return or at a minimum get a portion of their money back. This misalignment, coupled with a lack of control of the company post financing, further adds to the founders’ concerns.

While a preferred liquidation preference is considered “market,” there is no reason why the standard liquidation preference can not be modified to lessen the impact of the overhang. It is the rare founding group that has the leverage or nerve to test the limits of what terms the venture investors may be willing to accept. Notwithstanding this fact, there is ample precedent in the venture community for exceptions to the standard liquidation preference described above. Like all terms, this one too is negotiable. The liquidation preference provisions can be modified in several ways to be more attractive to founders. The good news for the venture investor is that the variations need not have a significant or adverse impact on their return on investment. The savvy investor can offer to modify the standard liquidation preference rights for the benefit of the founders without realizing much if any direct impact in many scenarios- a true “win win.”

Special Common Stock. As a starting point in exploring this alternative approach, investors need to understand that like preferred stock, common stock can be split into different classes, with certain classes enjoying special rights. In fact it is not uncommon for an emerging company to have two classes of common stock, one that votes and one that does not. Distinctions between classes of common stock can also be drawn along economic lines. For example, the founders’ stock could be set up (or reclassified if it already exists) into special common stock that carries with it a liquidation preference that is different than the other common stock. The idea of creating a special class of common stock for the founders is the basis for a range of approaches that can reduce the impact of the liquidation preference overhang described above.

Determining the Amount of Preference. If an investor gets comfortable with allowing a special class of common stock that carries a liquidation preference, the next question is what the dollar value of this preference will equal. No established rules or parameters exist regarding the appropriate dollar amount of this type of preference.2 From the investor’s perspective, the special liquidation preference would be an amount that is attractive to the founders but that does not significantly impair the investors’ return. If the founders have put in significant capital, the amount of this capital might be the appropriate number for the liquidation preference. Another approach is to set the liquidation preference at an amount that is equal to the pre-money valuation agreed upon with the investors as this amount is presumably some measure of the value that was created by the founders prior to the funding. A third possible approach is to take the total number of shares that will be owned by the founders, post-funding, and multiply that number by the price per share of preferred stock. This third approach eliminates the value associated with the option pool (the shares of which are generally considered part of the pre-money capitalization for purposes of pricing the preferred), and is arguably the truest indication of the value that the founders created through their sweat equity and other contributions prior to the venture investment. In the end, the amount that will determine the special liquidation preference is a matter up for negotiation.

Determining the Priority of Payment. Once the value of the special common preference is established, the next question is to determine how this liquidation preference gets paid out relative to the investor preferred and the other common stock. Again, no established rules exist to explain how the special founder stock should participate in a liquidity event relative to the other capital stock. While there is little data available from which to draw, the most typical approach seems to be to establish a special common stock that is junior to the preferred stock, but senior to the other common stock, in terms of liquidation preference, and not participating regardless of whether the preferred is participating or non-participating. While the above approach is the most common, many other possibilities could be considered when structuring a special common liquidation preference. For example, the liquidation preference could instead be senior to the preferred. A senior liquidation preference would eliminate the risk that the founders would get nothing in a liquidity event, and therefore greatly mitigate the overhang risk, because the founders’ common liquidation preference would always come off the top. Alternatively, the special common liquidation preference could participate alongside the preferred (so called “pari passu”). In addition, in any of the foregoing cases the special common stock could be either participating or non-participating once its liquidation preference has been satisfied.3

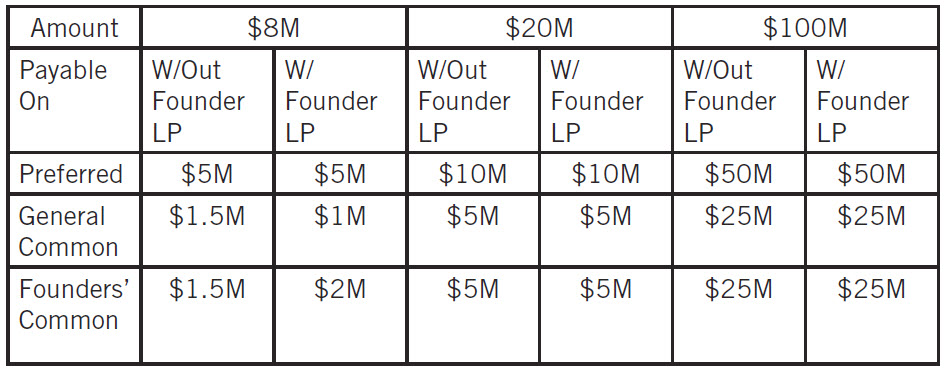

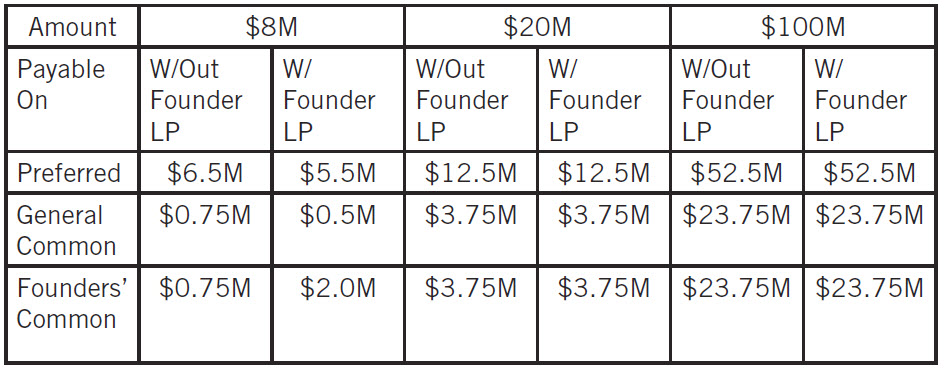

Illustration of Impact on Preferred and Common Return. The following tables show how the return to the investors, founders and other holders of common stock can be affected by introducing a special class of founder common stock with a liquidation preference. Both tables assume the following facts:

- investors have put $5M into the company, and therefore have a $5M liquidation preference, for 50% of the common stock on an as-converted basis,

- the founders own 25% of the common stock on an as-converted basis,

- the other common shareholders own 25% of the common stock on an as-converted basis,

- the liquidation preference on the special common stock is $2M, and

- the special common stock is non-participating.

The first table shows the distribution of proceeds when the preferred stock is non-participating, and the second table shows the distribution of proceeds when the preferred stock is participating.

The rows show the proceeds payable to the investors (“Preferred”), the founders (“Founders”) and the holders of other common stock (“General Common”) at 3 different sales prices — $8M, $20M and $100M. Under each price, the column to the left shows how proceeds would be distributed assuming there is no special class of founder common stock (“W/Out Founder LP”), and the column to the right shows how proceeds would be distributed assuming there is a special class of founder common stock (“W/Founder LP”).

Table 1. Non-Participating Preferred

This first table shows that the special common stock results in a transfer of value only at the $8M sales price. In this case, $500,000 is transferred away from the other common and to the founders. There is no impact on the preferred stockholders.4

Table 2. Participating Preferred

This second table shows that under the same range of scenarios in which the preferred stock is participating, the special class of common stock results in the transfer of $1.25M to the founders — $1M from the preferred stockholders, and $0.25M from the other common stockholders-only at the $8M sales price. The special common stock has no impact on the return to either the preferred stock or the other common stock in any other scenario.

Summary of Impact of Special Common Stock on Investor and Common Return

Impact on Liquidation Preference of Preferred. If the special common liquidation preference is subordinate to the preferred, the common liquidation preference will have no impact on the preferred liquidation preference as it will always, by definition, be paid after the preferred stock liquidation preference. The venture investors will always get their original investment back first irrespective of this common liquidation preference.

Impact on Return of the Preferred. The special liquidation preference can have an impact on the overall return to the preferred stockholders above and beyond their liquidation preference. The extent of the impact on the preferred return will depend on whether the preferred stock and the special common stock is participating or non-participating. If the special common stock is subordinate to the preferred stock and non-participating as in the above example, the impact on both the preferred stock and the other common stock will occur mainly at low end sales prices and at the higher sales prices their will be no impact.

Impact on Return of the Other Common Stock. The return of the other common stockholders can also be negatively impacted by introducing a special class of common stock with a liquidation preference. The entire burden falls on the other common stockholders until the preferred stockholders liquidation preference has been satisfied. After that, the burden is shared by the other common and the preferred stockholders.

Other Considerations

Tinkering with special common stock in the ways previously described raises several other practical questions. One is whether the idea of a special preferred stock is fair to the other class of common stockholders. As demonstrated above, the impact need not be significant on the other common stockholders who hold general common stock.

In addition, if a company is going to implement a special class of common stock, there are some important timing considerations. If there are other common stockholders at the time of the funding event, then under corporate law all such holders would need to have their common stock converted to special common stock as well. The conversion could not be “selective”. The same might also apply to shares subject to an option plan if there are any. In addition, converting general common stock to common stock with a liquidation preference could be a taxable event to the recipients of the special common stock. Both of these facts suggest that if the founders think they might want this structure in place at the time of a venture round, it may make sense to put it in place early on, possibly even at the time of the formation of the company.

Another question is whether the founders should vest in the special common stock. Imposing vesting would reduce the risk that one or more founders would decide to leave the company prematurely. Related to this is whether, should a founder leave the company without having fully vested in the special common stock, the special liquidation preference should be reduced or be effectively re-allocated to the remaining founders. This would be a way of transferring value from one founder to another-an additional benefit that can be conferred on the founders to sweeten the deal.

One final but important issue that special common stock raises is the impact that this special common stock may have on the ability of the company to raise subsequent rounds of financing. The company, the founders and the investors should understand that the special common stock would be a separate class of stock, and that under Delaware law no adverse change may be made to that class of stock without the consent of the holders of this class — i.e. the founders. Given that founders sometimes leave the companies they start, affording them this leverage might be a risky proposition. For example, future investors could require that the special common stock liquidation preference, as well as other preferred preferences, be given up as a condition to funding.5

Conclusion

While creating a special class of common stock for the founders with a special liquidation preference is not typical, it is an option that offers investors a great deal of flexibility and creativity. A special founder common stock can be structured in such a way that it has minimal impact on the preferred stockholders and the other common stockholders under most scenarios. The benefit to the founders, and the cost to the preferred stockholders and other common stockholders, would occur mainly at sales prices on the low end of the spectrum. Founders who are concerned about this type of downside protection, and feel that they should share more equitably in such scenarios, might find a special class of common stock to be a compelling feature. Investors willing to allow founders a special common stock may find that this concession allows them to attract better deals, especially in a competitive environment. In the end, what really makes a venture portfolio is the number of quality investments, not the downside protection. If a fund were to widely use a special class of common stock over a portfolio of 20 companies, 5 of which are sold in scenarios that cost the investors $2M each, the total cost to the fund would be $10M. But if the fund is able to attract just 1 more deal that returns a multiple of their investment, the loss of $10M would seem inconsequential.

For more information on the special founder liquidation preference, please feel free to contact Jonathan D. Gworek.

Footnotes.

1. For a more complete discussion of the liquidation preference overhang issue, see “The Liquidation Preference Overhang“, by Jonathan D. Gworek and Jeffrey Steele.

2. For preferred stock, the liquidation preference is equal to the original dollar amount invested, plus in many cases a return on that original investment. This “dollars in” approach does not provide a useful basis for establishing the founders’ liquidation preference unless the founders have put in a significant amount of capital themselves. It is therefore necessary when setting up special common stock to “pick” a liquidation preference amount.

3. In any case it is likely that the special common stock would need to be convertible into general common stock. If the special common stock is participating, it needs to be convertible, or deemed converted, in order to participate. Also, if the special common stock is non-participating it would need to be convertible into general common stock or the founders’ upside would be capped at its liquidation preference.

4. The table illustrates the outcome based on just one set of facts. While none of the scenarios impact the preferred return, there are situations in which the preferred return would be negatively impacted by the special common stock liquidation preference. This will be true in any case in which the special common stockholders percentage of the sale proceeds on an as-converted basis is less than their liquidation preference and the percentage of the sales proceeds that the preferred would receive on an as-converted basis after deducting the common liquidation preference is less than the preferred liquidation preference. This results from the fact that if the amount that the special common would get on an as-converted basis after the liquidation preference is paid to the preferred stockholders is less than the special common liquidation preference, the holders of the special common stock will opt to take their liquidation preference. The preferred stockholders would then, on an as-converted basis, receive their pro rata share of what is left after the special common stockholders take their liquidation preference. As a result, the preferred stockholders might in certain situations choose not to convert and instead take their liquidation preference whereas without the special common stock liquidation preference to consider they would have been better off taking their as-converted share. For example, if the table labeled “Non-Participating” were re-run using a $5M common liquidation preference with all other variables remaining the same, at an $11M sale, the preferred would convert and take $5.5M in the absence of a special common liquidation preference. However, if the preferred were in fact to convert, the special common would opt instead for their $5M liquidation preference which is greater than the $2.75 the special common would get if they opted to convert into 25% of the common. This would leave only $6M for the preferred and the other common stockholders to share on an as-converted basis, of which the preferred would take 2/3 or $4M. Since this is less than their $5M liquidation preference, the preferred would not convert but instead take their $5M liquidation preference leaving them $0.5M less than they would have received if there had not been any special common stock. To eliminate this transfer of value away from the preferred stockholders, the special common stock could be subject to conversion in those scenarios in which the preferred stock would, in the absence of the special common stock preference, be deemed converted to common stock.

5. While there certainly are scenarios in which the founders may be able to throw up barriers if they hold a special common stock, they should not be able to limit or block the ability of the company to raise subsequent venture rounds that are senior in liquidation preference to the special common stock. In anticipation of those future scenarios in which investors condition funding on the elimination of the special common stock liquidation preference and all other liquidation preferences (i.e. a cram down or recapitalization), the security could be structured in such a way that it converts to common stock if the venture preferred converts to common stock, or upon other triggers.

-

- Name/Title

- Direct Dial

-

-

Jonathan D. Gworek

Member - 781-697-2229

-

Jonathan D. Gworek